By Colin Lewis, Head of Strategic Advice, Fitzpatricks Advice Partners

April 2025

Super ideas for managing volatility

Shockwaves have been sent through the world’s equity markets with the introduction of sweeping tariffs by the Trump administration.

Whilst most superannuation balances have taken a shellacking, it’s important to remember that super funds are investment vehicles – tax structures.

Super’s not the problem – it’s what you invest in (shares, property, cash etc.) that determines how your wealth fares regardless of whether you’re investing inside or outside super.

Whilst easier said than done, now’s not the time to throw logic out the window when it comes to investing in super as a disciplined contributions strategy remains compelling even when markets are moving against you.

You may be reluctant to invest and stop making voluntary concessional contributions, but super is for the long haul, so unless you’re about to retire, you have years – maybe decades – for markets to recover and short-term volatility can be a good time to top up as assets are cheaper.

Waiting may mean missing the upside when markets inevitably recover.

Pre-tax concessional contributions

When you make a voluntary concessional contribution to super – whether as a personal deductible contribution or via your employer as a salary sacrifice contribution – you’re putting money away for retirement.

Whist this is the objective of superannuation, let’s be honest, the real motivation is to save tax – otherwise you’d make an after-tax non-concessional contribution.

A tax benefit arises where the 15 per cent tax paid on the contribution (30 per cent for high income earners) is less than the tax you pay on your taxable income outside super – whether salary and/or investment earnings.

So, don’t make a voluntary concessional contribution if your income is less than the effective tax-free threshold of $22,575, or if you’re eligible for the seniors and pensioners tax offset, $35,813 (single) or $31,888 (each member of a couple) otherwise it’s costing you to put money into super.

And if you earn more but less than $45,000, there’s little to no benefit with the current 16 per cent tax rate.

If you’ve received a tax benefit from making a concessional contribution, then be comforted in knowing that you have a buffer from the current downturn in global equity markets.

Your tax saving insulates (protects) you from losing money when markets fall, and they must fall a lot before you’re worse off from having made the contribution in the first place.

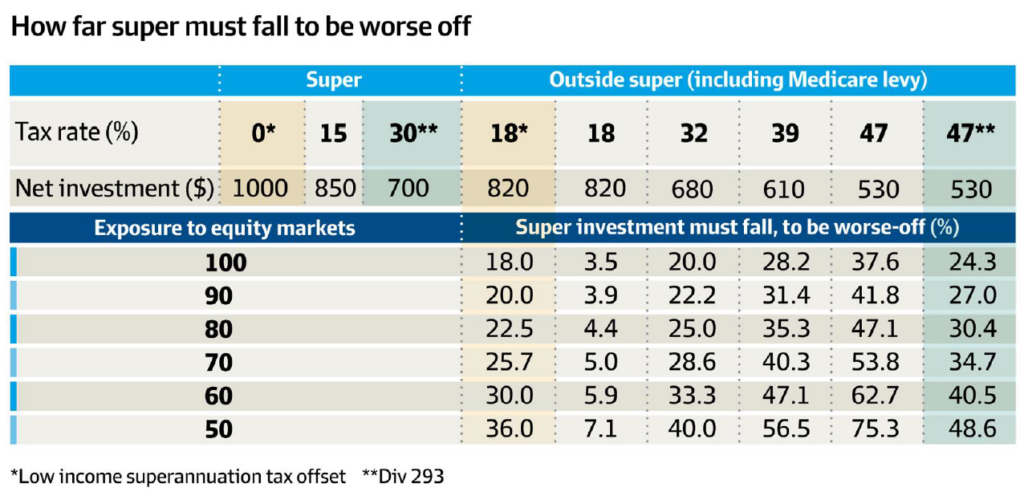

Take Fred, Wilma and Betty who are on tax rates of 32, 39 and 47 per cent (including Medicare levy), respectively.

By making pre-tax contributions, they put 85 cents of each dollar they earn to work in super. But if they each paid tax and invested personally, then only 68, 61 and 53 cents respectively would be working for them.

This tax benefit – difference in tax rates – makes it hard for them to lose money.

The tax saving from contributing to super means Fred’s investment must drop 20 per cent before he’s worse-off from having made the contribution.

In Wilma’s case, her investment in super from the contribution must fall 28 per cent before she’s worse off and for Betty it’s 38 per cent.

It’s highly unlikely for them to be invested entirely in equities. Most Australians have a balanced investment mix – around 60 to 70 per cent in shares and property – or a growth investment mix – around 85 per cent in shares and property.

So, the decline in equity markets needs to be even greater for Fred, Wilma and Betty to be worse off – assuming other asset classes haven’t fallen simultaneously.

Assuming they all have a 70 per cent exposure to equities in super, the market must drop 28 per cent for Fred, 40 per cent for Wilma and 54 per cent for Betty, to be worse off – and as bad as it’s been lately, this hasn’t happened.

If they’re all wage earners, this applies equally to their employer’s compulsory superannuation guarantee contributions – markets must drop by these percentages before they’ll lose money on these contributions.

Then there’s Barney on a tax rate of 47 per cent (including Medicare levy) but his combined income and concessional contributions exceed $250,000, so he pays an extra 15 per cent tax on contributions over this threshold – division 293 tax.

So, while Barney is on the top tax rate like Betty, his investment in super from a personal deductible contribution must fall 24 per cent before he’s worse off.

But if Barney is a wage earner, up to $29,932 of his $30,000 concessional contributions cap will be gobbled up by his employer’s superannuation guarantee contributions leaving him little to no scope to top up – unless he has unused cap amounts from previous years and had a super balance less than $500,000 at 30 June 2024.

Markets must drop 35 per cent before Barney loses money on his employer’s contributions (with 70 per cent in equities).

Dollar cost averaging

Superannuation guarantee and, generally, salary sacrifice contributions are made regularly by your employer.

Regular deposits into an investment at regular intervals over a period – known as dollar cost averaging – is a powerful way to invest.

It can reduce the risk of investing in volatile times and helps avoid the pitfalls of attempting to time entry into markets – allowing you to build exposure to growth assets in a disciplined way.

So, whilst wage earners can’t do much about their employer’s compulsory contributions, there should be comfort in knowing that dollar cost averaging is at work

And with your own voluntary contributions, it’s important not to lose faith and reduce, even cease them when markets are weak because that’s when dollar cost averaging works best.

In volatile times like now, the tax benefits of super make it compelling to stick with a disciplined contributions strategy, especially when it’s done in conjunction with dollar cost averaging.