10 lessons Cressida Campbell taught me about art

By Graham Hand on behalf of Firstlinks

October 2022

I don’t know much about art generally, but I know a lot about Cressida Campbell, whose career and work I have followed closely for at least 25 years. It is a coming-of-age event when an artist is chosen for a long exhibition at the pinnacle of Australian art, the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in Canberra. Campbell recently started a remarkable five-month run from 24 September 2022 to 19 February 2023, and 140 of her works show her evolution to a master of her technique over the last 40 years. I can barely contain my excitement about attending. Here is the cover of the NGA book produced for the exhibition.

I bought my first Campbell piece on eBay for $120, an early, unique screen print, but it was only when she released a beautiful, large format book of her collected woodblocks in 2008 that I became enthralled. The print run of the first edition of “The Woodblock Paintings of Cressida Campbell” was only 1,000 copies, and it quickly sold out. I grabbed the last copy from Dymocks for $100, then bought another privately online for $120. The book has subsequently been reprinted in small runs but when the first edition comes up at auction, it sells for $2,000-plus.

My fascination was complete after a small exhibition in February 2009 at the S.H. Ervin Gallery in Sydney. We had to queue to enter, which was a guide to her popularity. My knowledge of art was limited to politely accompanying my wife to galleries, mainly wondering how long we needed to spend there before doing something interesting. But Campbell’s work was different and resonated strongly, and I now own about 18 prints and woodblocks, mainly the cheaper, early pieces. I say ‘about’ because some are in storage.

Her major woodblocks sell at auction for over half a million dollars. In March 2022, an early Campbell woodblock painting from 1987 called “The Verandah” sold for $515,455 (including buyer’s premium) at a Menzies auction in Sydney, as the headline below from The Australian Financial Review shows. It sold originally for $2,500 and had never come up for auction before. There are 99 prints available at more accessible prices of about $15,000 to $20,000 each when one appears at auction.

Art is big business, for investment and pleasure

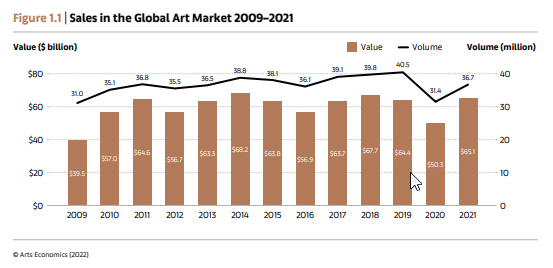

UBS produces an annual Art Market Report, and the 2022 edition reports that following a COVID slump in 2020, the global art market recovered strongly in 2021. Although it’s not an easy market to track, UBS places the aggregate sales of art and antiques by dealers and auction houses in 2021 at an estimated $65.1 billion, up 29% from 2020, and above pre-pandemic levels. Far more of the auction action now takes place online.

Art is increasingly seen as an investment as well as for its visual appeal. In a 2021 report on Art as an Asset Class, Deloittes said:

“there is a growing recognition of art as an investment class by investors. People become more sophisticated in their financial and estate planning, and they begin to view art as an investment.”

Although I love Campbell’s work, my background means I cannot avoid thinking about her art in investment terms as well as aesthetic value. One reason I expect her work to continue to increase in price is that her output is modest while her profile skyrockets. There are simply not enough pieces available to satisfy demand at anywhere close to past prices.

According to the NGA exhibition book, her meticulous process allows only five or six new works a year, and they are snapped up before they appear in public. A recent exhibition at Philip Bacon Galleries in Brisbane, his first with her for five years, sold out to his clients three weeks before opening, with 300 people on the waiting list. As Bacon told The Australian Financial Review, in the time between his two exhibitions, the market for her work has “seismically shifted”.

Campbell’s process is time-consuming and meticulous. Briefly, she draws her subject from life onto a piece of plywood with great precision, then using an engraving drill, she carves into the image along the drawing lines. She applies watercolours to the work within the carved sections, preventing the colours from running. From the final painted woodblock, she produces a unique print by dampening the painting and using rollers on the back of the paper to lift the image from the woodblock.

For the last three decades, she has produced single prints only, and she sells the woodblock and the print. A few earlier works were reproduced in print runs of up to 99, making them more affordable, but her recent work sells at dealers for over $300,000 for both the painted woodblock and the unique print.

Here are some brief lessons from my decades of watching Cressida Campbell’s works sell at galleries and auctions, but of course, these may not apply equally to all artists. Maybe I was lucky.

Lessons from collecting Cressida Campbell

Most advisers on collecting art will start with the motivation or intentions, and say people should buy what they love then they can’t go wrong. I take more of a value approach. There’s little reward in paying $10,000 for an artist whose work normally sells for $1,000 even if a collector loves it. But unless a piece is bought for storage and resale, it is certainly true that art should bring joy and a buyer usually has to live with it on their wall.

1. You don’t need to know much about art to become a collector

Can a specialist work in heart surgery without knowing how the entire body works? Does any fund manager select stocks in isolation from the economic and market environment? Probably no to both, but art is different. Some people may think they need to have a good overall art knowledge before buying a particular artist, but I know little about art generally. I paid around $500 for early Campbell pieces many years ago because I liked them, but I was also confident that she would develop a big following based on the reaction to her book and exhibition. Now I attend auctions to watch the market for her work and I know more about other artists that come up, although I have no intention of widening my interests.

2. You should like the work

While it’s possible to invest in art purely based on price, supply and demand, the market is not assured and interest in artists can come and go. Prices are not immune from economic impact. There’s little downside in buying art you love to decorate a room or brighten a space or because it speaks to you at a deeper level, and if owning and living with a piece is enjoyable, the price is less relevant.

3. Auction guides are often wildly inaccurate

In the early days, I missed out on some pieces as I read the upper level of the auction price guide as my budget. A painting would be promoted as $3,000 to $5,000 and sell for $8,000. I gradually realised that at least for Campbell, the auctioneers and dealers were behind the public. As her work rose in price, the professionals seemed to be at the previous auction. Even when I knew the upper range would be left far behind and set myself a bigger budget, more enthusiastic bidders would sometimes pay whatever it needed. Now, the upper estimate might be $200,000 and it sells for $250,000.

4. Don’t worry if an artist is labelled ‘popular’ or ‘commercial’

The prices of some artists do not rise quickly because they are labelled ‘popular’. This seems to apply to the work of Campbell’s great friend, the late Margaret Olley. The Art Gallery of NSW owns many Campbell works but I have never seen them displayed. When I have asked the Gallery where the works are, they explain that their entire collection is many times larger than what can be exhibited, and Campbell’s pieces are in storage.

There is a revealing paragraph in the new NGA book which also shows how experts lagged the public:

“Campbell has made her way, almost be stealth, to the first rank of contemporary Australian artists. This is despite museums and public institutions having been slow to recognise her achievements, and comparatively little has been written about her work. Her popularity with private collectors has possibly worked against her in this regard, leading to the lazy assumption that she is a ‘decorative’ or ‘commercial’ artist. This may be partly because she came to maturity as an artist at a time when Australian museums and media were preoccupied with the local outgrowths of postmodernism – with art theory, appropriation, and a wide range of self-conscious avant-garde activities.”

Sometimes, the less you know, the better. Campbell and her fans have no such pretensions.

5. Watch all sources and auctions

With negligible new supply publicly available from Campbell, there are three potential sources:

Private sale on sites such as eBay and Gumtree. It’s possible to find Campbell pieces here but they often appear expensive. A quick search when writing this article showed “Resting Butterfly” for $67,500 and “Bush Objects” for $27,500. Even with my enthusiasm and experience, these look pricey to me, but critically, I don’t love either piece.

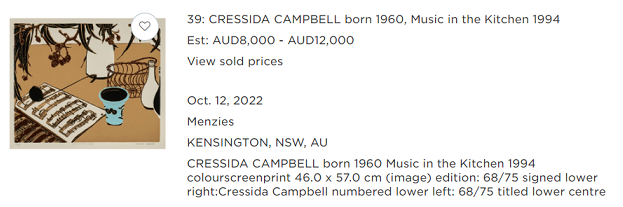

Auctions regularly feature Campbell art. The major houses such as Smith&Singer (formerly Sotherby’s), Deutscher and Hackett and Shapiro are normally top-end and buyers should expect to pay high prices, often above the upper estimate. Recent sales of around $200,000 for unique prints and woodblocks are common. But where a piece such as “Music in the Kitchen” is from a print run of 75, it’s still possible to pick one up closer to $10,000, perhaps from a smaller auction house.

Art dealers handle occasionally new or resale works but tend to reward their best clients first, and the general public can join long waiting lists but never hear from a dealer.

6. Stay ahead of price rises

Yes, research the value and know the market, but Campbell is so rare that overpaying may be required for a beautiful piece. It seems strange to make a case for paying too much, but it may be the price of entering this game. If a collector becomes familiar with Campbell’s work, they may need to trust their instincts to beat the opposition.

7. Focus less on buyer premiums and commissions

For anyone with an investment background, 4% entry fees for managed funds are now consigned to the history pages, and ETFs with fees of 0.05% make active managers at 1% look expensive. These fees are nothing compared with the art world. The buyer’s premium at auction is usually around 22% to 25%, it can be a shock and needs to be factored in, but it’s a fact of life if a desirable piece appears. Still, bidding $40,000 and knowing the end price will be over $50,000 takes a bit of getting used to.

8. Learn what is available

Unique works like new woodblocks and prints are one-off and expensive, and as “The Verandah” auction showed, even her older works now attract big money. Beginners may prefer to target the early works produced in larger print runs. However, what is not widely understood is that an artist like Campbell did not necessarily print the full quantity suggested by the reported records. Printing on high quality paper with watercolours is expensive and highly time-consuming for a struggling artist.

While the print run may be recorded as 20, such that the bottom right of a print may say 1/20, Campbell may have printed only 10 copies for sale. In the early days, if they were difficult to sell, they may go into a cupboard as she moved on to another work. A leading dealer told me her early works are not as common as widely believed. Nevertheless, limited edition prints are a great way to begin an art collection.

9. Buy the best you can afford

Do you intend to buy one original, valuable artwork a year, or many lower-priced pieces? My main mistake in collecting Campbell (and yes, I am saying this with hindsight knowing her work has appreciated) is that I tended towards the cheaper pieces rather than hitting whatever the auction price required. I have a particular regret about “Through the Windscreen”, shown below, which I had the chance to buy in the early days and now is worth multiple times more. It is supposed to be printed in a run of 20 so there should be plenty out there. If you have one, contact me.

I’m intrigued by the mistake she made. Can you spot it? The woodblock is the mirror image of the print. This print shows a scene in Australia so the steering wheel should be on the right-hand side, especially as the numbers on the dial are not reversed.

“Through the windscreen”, the one that got away:

10. Art has a valid role in a portfolio but is often not for sale

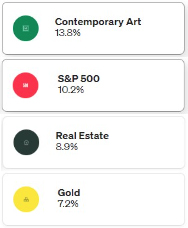

I hesitate to quote returns from collecting art as there is so much variation, and although there may be vested interests, there are many results arguing that good art outperforms other major asset classes. Here are the claims for contemporary art (such as the well-known Banksy) price performance for 1995 to 2001. Make sure you like the work first and then invest in it. But you may never sell a great piece, as it becomes part of your life and home. I can’t see a circumstance where many of my Campbells will see the market.

Art is subjective and so are you

Collecting art is a subjective experience but hanging a painting or another object on your walls says something about you. Whenever I walk into someone’s house, I now pay far more attention to the art than I used to. Most people want to tell the story of where the art came from and why they chose it, so don’t ignore it.

And get along to Canberra to see Cressida Campbell, and learn what all the fuss is about. You might not know much about art, but you’ll know what you like.

*Graham Hand is Editor-At-Large for Firstlinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any person. Images of works are copyright Cressida Campbell.