Why our financial abilities peak at age 53

By James Gruber on behalf of Firstlinks

November 2022

I happened upon an interesting book about how our financial abilities start to decline quite early in age and what we should do about it. The book is called What to do when I get stupid and it’s by a US economist, Lewis Mandell. Here is an overview of Mandell’s findings with my thoughts interspersed.

Mandell cites a plethora of scientific studies which suggest our capacity to make financial decisions peaks around the age of 53.

He first distinguishes between ‘fluid intelligence’ and ‘crystallised intelligence’.

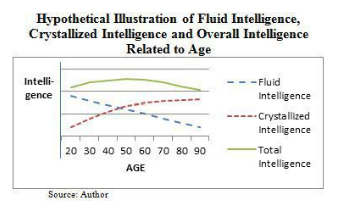

Fluid intelligence is the ability to think abstractly and deal with complex information. Psychologists have long known that fluid intelligence peaks about age 20 and declines by 1% each year thereafter. It’s why great mathematical discoveries tend to be made by younger scholars, for instance.

As we age, however, we also gain experience to help us make better decisions. This is called crystallised intelligence. Thus, while fluid intelligence decreases with age, crystallised intelligence increases:

Since fluid intelligence declines at a slow but steady rate, overall intelligence will tend to increase at first, boosted by the relatively quick increase in crystallised intelligence, but then begins to slow down in middle age. The constant loss of fluid intelligence begins to match the smaller and smaller increases in crystallised intelligence, until the increases and decreases are equal, at which point our overall intelligence peaks.

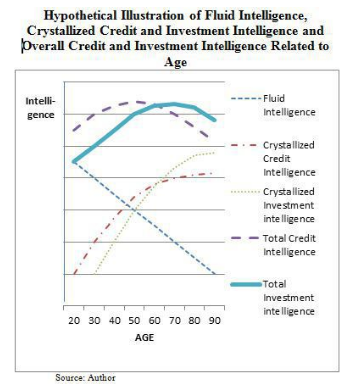

When you combine the two types of intelligences and apply them to financial decisions, research indicates that we peak around age 53 and decline thereafter at a rapid rate. The age for peak performance varies according to different financial products, from a low of 45.8 years old to a high of 61.8 years.

Decisions related to borrowing and debt peak at around age 53 while investment skills peak around age 70. The difference is likely due to the varying ages at which we get experience in borrowing and investment. When we’re young, we don’t have much money and therefore will rely on debt to fund a house, for example. When older, and perhaps thinking about retirement, we’re more likely to have accumulated assets and are more open to learning about investment.

Get prepared now

Only a small number of us will reach 80 years of age without some kind of mental impairment that will cloud our financial decision-making. But our self confidence in our financial decision-making increases with age. Older investors are more prone to use new investment information from television and newspapers, yet they’re less skillful in using the information and are more likely to increase the risk profile of their investments as a consequence.

Mandell believes it’s wise for us to take financial decision-making out of our hands while we still have the mental capacity to do so. He thinks planning is critical to guarantee we’ll have enough income coming in each month for the rest of our lives to maintain our desired standard of living.

He advocates a guaranteed income that should be regular, virtually impossible to lose and should increase as our expenses increase with inflation. And it should last no matter how long we live.

Threats to this planning include low interest rates, stock market volatility, rising inflation and ourselves if we rely on our own decision-making as our faculties age.

The best strategy

The goal is to have enough money coming in each year to cover our core retirement expenses. Beyond that, any additional income is discretionary. They are surplus assets which can be used to increase our standard of living.

If the income coming in each year isn’t enough to cover retirement expenses, there are two choices: 1) reduce our standard of living, or 2) gamble on risky assets to make up the shortfall. Many people opt for 2).

Mandell goes into how to calculate core retirement expenses, including identifying which ones will increase with inflation.

Much of his solutions to the problem are US-centric. Broadly though, he suggests a mix of fixed annuities and Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS).

First, he likes fixed annuities where you pay in a sum of money and get a fixed monthly payment for life. By doing this you: 1) eliminate market risk 2) since these annuities pay for the rest of our lives, they eliminate longevity risk and 3) since they can’t be cashed in, they eliminate judgment risk.

He thinks TIPs are a useful hedge against inflation. An additional strategy to reduce the impact of inflation is to try to retire debt and rent free. And owning a low-cost maintenance home and car are also important.

The book examines ways to protect assets against irrational judgments that you might make. This includes such things at joint accounts, splitting assets etc.

If you manage your own investments, there is little legal protection against irrational decisions that one might make in future.

Conclusion

The statistics on declining financial abilities may have surprised you as they did me. Of course, in Australia, we have a generous pension and superannuation system, which both help in funding our retirements. Nonetheless, it’s useful to at least consider Mandell’s point of automating much of our financial decision making before our cognitive abilities start to wane.

*James Gruber is an Assistant Editor at Firstlinks and Morningstar.