Managing sharemarket volatility

By Colin Lewis, Head of Strategic Advice, Fitzpatricks Private Wealth

August 2024

At time of writing, fears of recession in the US sparked global panic selling with leading share indices tumbling.

Wall Street suffered its worst day in nearly two years before surging days later to its best day in two years.

The Australian share market suffered its worst day in more than four years and is still well down.

Japan’s Nikkei plunged in its worst day since the Black Monday crash of 1987 before bouncing back.

Just weeks earlier, many indices scaled record highs – it’s a rollercoaster ride.

We live in turbulent times, but – whilst easier said than done – you shouldn’t throw logic out the window when investment markets are volatile.

The tax benefits of superannuation and the risk-mitigation and potentially cost-cutting benefits of ‘dollar cost averaging’ mean that sticking with a disciplined contributions strategy remains compelling even when markets are moving against you.

Whether you invest via a super fund or personally outside super, it’s what you invest in – cash, shares, property etc. – that determines how your wealth fares.

Remember, a super fund is an investment vehicle, not an asset class, and being a structure, does not lose you money.

When markets are volatile, you may be reluctant to invest and stop making voluntary contributions. But super is for the long haul, so unless you’re about to retire, you have years – maybe decades – for markets to recover. And short-term volatility can be a good time to top up as assets are cheaper.

Volatility can lead to anxiety and it’s easy to just ‘wait and see’. You may try to time the bottom of the market – good luck – or wait until confidence returns before investing. Ironically, when markets recover, many investors wait for the market to fall again in the hope of picking up bargains.

These approaches are flawed and can create ‘investor paralysis’ where delaying investing may mean missing the upside when markets inevitably recover.

Finding ways to invest which manage emotions is important in achieving long-term goals.

Dollar cost averaging

Making regular deposits into an investment at regular intervals over a period of time – dollar cost averaging – is a powerful way to invest.

It can reduce the risk of investing in volatile times and helps avoid the pitfalls of attempting to time entry into markets.

Dollar cost averaging overcomes ‘investor paralysis’ by giving you the opportunity to build exposure to growth assets in a disciplined way.

Take Fred and Wilma, who each have $100,000 to invest in a managed fund – which entails purchasing ‘units’ representing the value of the fund’s underlying assets often comprising Australian and international shares.

Fred invests all in one go when the unit price is $1.00 and gets 100,000 units. The unit price then dives to $0.70, and his investment is only worth $70,000. It gradually recovers to $0.80 then $0.90 and finally to $1.10.

Patience is a virtue and with Fred, it paid off as his investment is worth $110,000.

Wilma, on the other hand, is apprehensive about investing due to market volatility, but is prepared to invest her $100,000 gradually in equal instalments over the same set periods.

Wilma’s initial $20,000 investment acquires 20,000 units. The second $20,000 buys 28,571 units at $0.70. Her third $20,000 gets 25,000 units. Fourth, 22,222 units and final $20,000 gets her 18,182 units at $1.10. Wilma ends up with 113,975 units in the managed fund and has a better outcome because her investment is worth $125,373.

By committing to regular investment amounts, Wilma overcame ‘investor paralysis’ and purchased the managed investment units at a lower average unit price of $0.88.

When you commit to investing a fixed amount into an investment that varies in price, e.g. shares and managed fund units, you purchase more when the price is low and less when the price is higher – the essence of dollar cost averaging.

There is no guarantee returns will be maximised and it doesn’t mean you should never invest lump sums, but it potentially lowers the cost of investing and is a powerful way to reduce risk if you’re reluctant to stick to a long-term investment plan in the face of volatility.

The good news is that dollar cost averaging is how most wage earners invest in super via their employer’s regular compulsory superannuation guarantee (SG) contributions. In addition, most salary sacrifice arrangements are via regular contributions.

Whilst wage earners can’t do much about their employer’s SG contributions, they can about their own voluntary contributions and this is where it’s important not to lose faith and reduce, or even cease them when markets are weak, because that’s when dollar cost averaging works best.

Super

A feature of pre-tax concessional contributions is the buffer they provide from a market downturn due to the tax saving you get.

This tax benefit insulates (protects) you from making a loss when markets fall.

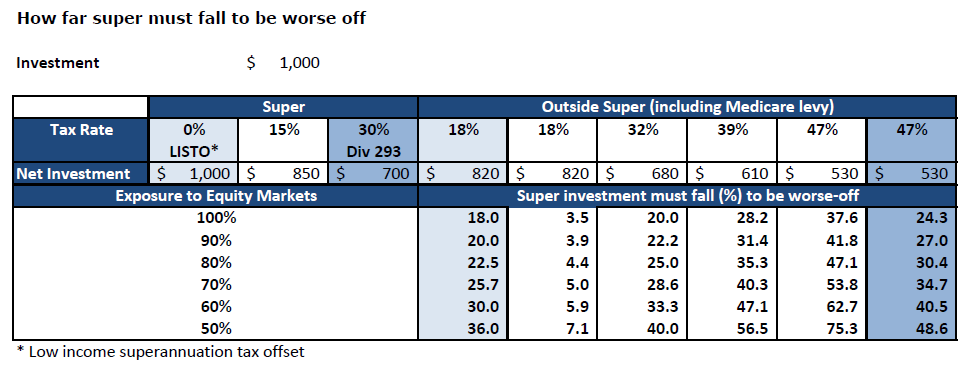

Take Luca, Jen and Sam who are on tax rates of 32, 39 and 47 per cent (including Medicare levy), respectively.

By making pre-tax salary sacrifice contributions, they put 85 cents of each dollar they earn to work in super. But if they each paid tax and invested personally, then only 68, 61 and 53 cents respectively will be working for them.

This tax benefit makes it hard for them to lose money.

The tax saving means Luca’s super investments must drop 20 per cent before he’s worse-off from continuing with his contribution strategy.

In Jen’s case, her super must fall 28 per cent before she’s worse off and for Sam, it’s 38 per cent.

Given it’s extremely rare for someone to be invested entirely in equities, the market decline needs to be even greater to be worse off – assuming other asset classes haven’t fallen simultaneously.

Assuming they all have a 70 per cent exposure to equities in super, the market must drop 28 per cent for Luca, 40 per cent for Jen and 54 per cent for Sam, to be worse off – and that hasn’t happened.

And this applies equally to their employer’s SG contributions – the market must drop by these percentages before they’ll lose money on those contributions.

Then there’s Abby, a wage earner on a tax rate of 47 per cent. Her combined income and concessional contributions are over $250,000, so she pays division 293 tax – the extra 15 per cent tax on contributions over that threshold.

There’s little to no scope to make voluntary concession contributions with SG contributions gobbling up her cap – unless she has unused cap amounts from previous years and had a super balance of less than $500,000 at 30 June 2024.

But with her employer’s SG contributions, the market must drop 35 per cent before she loses money on them (with 70 per cent in equities).

In volatile times, the tax benefits of super make it compelling to stick with a disciplined contributions strategy, especially when it’s done in conjunction with dollar cost averaging.